My aim in this second blog entry will be to offer a general overview of the most recent European policies on social enterprises and to go a little bit deeper on the approaches and understandings of social enterprises through a review of research carried out in Catalonia.

As I said in the previous blog post, even though policies oriented to the ‘Third Sector’ go back to the late 1980s, the core document, which most of current European policies regarding social entrepreneurship are based on, is the Social Business Initiative published in 2011. Since 2011, as the main European Commission web page related to social entrepreneurship observes (Supporting entrepreneurs and the self-employed – Social entrepreneurship), diverse policies and measures have been implemented and several initiatives have been carried out. Among them, significant contributions in the form of mappings and comparative projects, smaller reports focused on specific countries made in 2014, and further extensions carried out in 2016.

Image: Compilation of covers of different documents produced by the European Union about Social entrepreneurship.

After a non-systematic review of many of these documents it could be said that one of the core problems (which has theoretical, methodological, analytical and policy implementation consequences) has to do with the incommensurable diversity and richness that the concept of social enterprise tries to gather. The diversity and rhizomatic nature (Deleuze & Guattari, 2005, p.3) of the initiatives that “social entrepreneurship” tries to sum up in Europe has to do with the goals and philosophies of each initiative, its structure, organization and institutionalization level. But more importantly, this diversity is related to the ways in which the different Welfare States have been developed during the 20th century in Europe (Sping-Andersen, 1990). More precisely, the current multiplicity of forms that these activities show is directly related to the ways in which the productive systems (including cities and neighbourhoods), their working regimes, and their associated welfare systems, have been reshaped in the last thirty years. From this point of view, as I’ll argue, the different austerity measures implemented in the European States after the Global Financial Crisis would be the latest “update” of this trend (Lorey, 2015; Kelly and Pike, 2017; Alonso and Fernández Rodríguez, 2018).

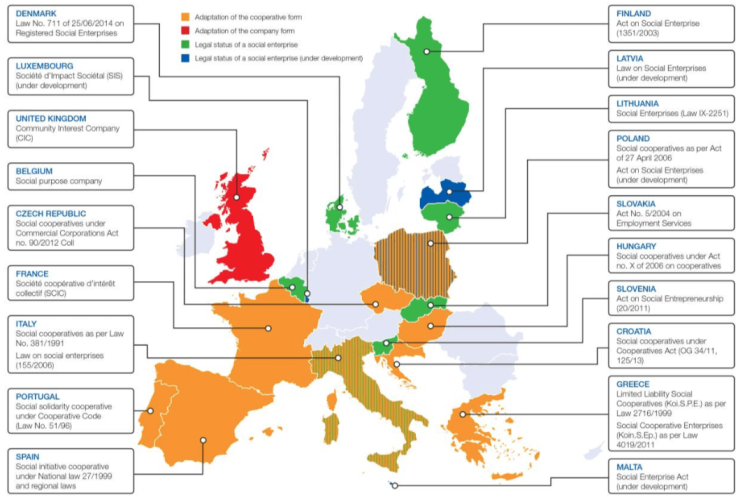

Social enterprises in the European Union

European countries with specific legal forms or statutes for social enterprises. Image retrieved from: A map of social enterprises and their eco-systems in Europe. p. 4.

To begin with, and broadening the definition of social entrepreneurship that I suggested in the last blog post, the European Commission uses the term to account for the following types of business*:

- Those for who the social or societal objective of the common good is the reason for the commercial activity, often in the form of a high level of social innovation

- Those whose profits are mainly reinvested to achieve this social objective

- Those where the method of organisation or the ownership system reflects the enterprise’s mission, using democratic or participatory principles or focusing on social justice

*For a more academic (and complex) operationalization of the notion that reflects the diverse understandings of social enterprises in Europe, it is worth reading the first part of the report: “Social enterprises and their eco-systems: developments in Europe” (Borzaga, & Galer, 2016: 8-13).

In the EU there are multiple legal forms that a social enterprise can adopt. They can operate as cooperatives; as private companies limited by guarantee (which some of them are mutual); and many of them are non-profit-distributing organisations (including provident societies, associations, voluntary organisations, charities and foundations). Operating in fields such as work integration, personal social services, local development of disadvantaged areas and collectives, environmental protection, arts, sports, culture preservation, etc., the concept covers a really wide “social field”. In the 20th century this space, at least in western industrialized countries, has been occupied by the church (or philanthropic collectives close to it), the welfare state, trade unions and a whole range of associations, including governmental organizations, some social movements, and diverse collectives (Baglioni, 2017, p. 2329). To some extent, it could be said that one of the main features of this “social field” was being “outside” the market – even though it was an effect of the market development in the industrialized states frame, and it operated, in some cases, as a functional externalization zone, and/or a reproductive area for it. In this sense, the notion of social enterprises fostered by the European Commission, as it stresses the business aspect of these activities, redefines this field placing it in the semantic area of the market driven economy. The closing slogan of the promotional video about these European social entrepreneurship policies makes it clear: “Business with a human touch” — implying that the EU now takes for granted, as a departure point, that “all of them are business”.

Video retrieved from: http://ec.europa.eu/social/main.jsp?langId=en&catId=89&newsId=2649

Social Enterprises in Europe: tensions, limits, possibilities

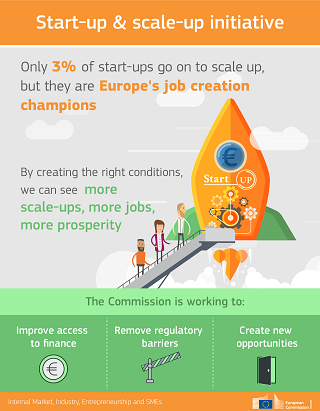

Many social-enterprises are structured and obey certain logics of alternative economies —solidarity, sustainability, fair trade, etc.— or have their origins in social movements. The imperative to adopt enterprise forms of management and a clear business ethos on behalf of arguments such as efficiency, is relatively new (at least in some countries). For example, the European Commission shows its determination to supporting social economy through The Start-up and Scale-up Initiative, a political “tool” designed for promoting, developing and growing conventional for-profit start-ups and small and medium enterprises:

Image retrieved from: http://ec.europa.eu/growth/smes_en

In this sense, the main proposals of this initiative revolve around the objectives of removing barriers for start-ups to scale up in the single market; creating better opportunities for partnership, commercial opportunities and skills; facilitating access to finance, etc. Overall, and as it was pointed out previously, while these kinds of support oriented to the market might be helpful for the institutionalization of some social-enterprises, there is no doubt that they can also be quite problematic for others. Beyond the possible contradictions with the socially oriented goals that are central to their missions, social enterprises “have proved to be resilient [to the Global Financial Crisis]” precisely because of their small size, their community based nature, their self-managing ability as small organizations and, very importantly, the personal commitment of their participants (an engagement of the employees that every conventional enterprise or public institution desires to have). In this vein, the “Social enterprises and their eco-systems: developments in Europe” (Borzaga, & Galer, 2016) report stresses that:

Social enterprises’ success factors only partially coincide with those of mainstream enterprises (…) neither legal recognition nor access to finance are per se sufficient conditions for boosting social enterprise multiplication. (…) Key drivers boosting social enterprise’s development and scaling up include a wider recognition on the part of national governments and the definition of consistent public policies, including public procurement strategies that fully acknowledge the special nature of social enterprises (…) (pp.45-46)

In this sense, the problems and debates regarding the definition of social entrepreneurship remains wide open, up to the point that in some contexts there are initiatives that explicitly refuse to be categorized in that way (Borzaga, & Galera, 2016: 17; Molina et al. 2017: 22). These cases show us that the category is by no means neutral. Thus, these sort of resistances have to be understood in a context where the rise of the concept in certain countries (as a top-down landing concept) is directly related with long term precarisation processes and the neoliberal reorganization of the Welfare State through a myriad of austerity measures. The arguments for fostering social enterprises that are given in an early policy brief shared by the European Commission and the OECD point out the displacement sketched in the closure of my previous post:

Working with social enterprises and promoting their development can result in short and long-term gains for public budgets through reduced public expenditures and increased tax revenues compared with other methods of addressing social needs. (p. 3 and p.12)

In this context, it is interesting to quote an argument about consequences of the former proposal as it is developed in the Editorial of a recently published special issue on Social Enterprises and Welfare regimes in Europe*:

[The social enterprise sector] has promoted genuine innovations in terms of increased capacity to reach specific vulnerable groups, as well as in terms of capacity to deliver new services. However, such an innovation has often been pursued in combination with public action retrenchment, sometimes helping to justify it, with consequences on people’s lives (…) (Baglioni, 2017 p. 2337)

* For anyone interested in this kind of debates (and conflicts) this publication is an important work that covers different European states with contributions of independent researchers.

Overall, the conclusions of the Spanish report Social enterprises and their eco-systems: A European mapping report, also written by independent academics, sums up quite effectively the main debates that are taking place around the growth of social-entrepreneurship both in Spain and in Europe:

The main discussion topics revolve around the position of social enterprises in relation to the social economy, the level of constraint on profit distribution, the source of funding to be considered a social enterprise, the need to create a social enterprise label and the economic role of these organisations. In all, these issues point toward the wider debate of whether social enterprises can best be understood as an innovative institutional tool for a new system of social welfare or as an excuse to justify the withdrawal of public authorities from the provision of certain services. (p. 50)

Social Enterprises in Catalonia

To further develop the idea that these grammars of enterprise have a “local vocabulary” or a “local dialect”, I will review some interesting empirical research centred on the social enterprises carried out in Catalonia (Spain) by a research group of the Autonomous University of Barcelona titled: Social entrepreneurship: local embeddedness, social networking sites and theoretical development.

To start with it has to be taken in to consideration that in Catalonia, as is the case in the Basque country, there is a strong tradition of co-operativism and social movements that somehow have operated as the substrate for the contemporary emergence and “success” of social entrepreneurship. Without that background it is difficult to understand the current configuration of the field of social and alternative economies in Catalonia.

According to the most significant works published out of this research (Valenzuela-García et al., 2015; Molina et al, 2017 —this one in English), one of the main events that explains the emergence of the concept of social entrepreneurship in Spain around 2010 has to do with the transformation of the Saving Banks (Cajas de Ahorros) into ordinary commercial banks. Saving banks were, historically, public, non-profit, financial institutions owned by the provincial governments and controlled by local political representatives. The original aim of Saving Banks was to encourage thrift among the very poor and the emerging working class, and their profits were reinvested in diverse social programs and welfare projects. In the last decades of the 20th century, thanks to the incentives of the governments, they evolved up to the point to compete with commercial banks, and in 2008 they still represented half of the Spanish financial sector. Even though they were not exempt from instances of corruption and complaints about dubious administration, they administered significant budgets for all kinds of social expenditures. Through direct and indirect public funding these financial institutions enabled and fostered areas of activity that were occupied by organizations from the “social economy” and the “third sector economy” (Valenzuela-García et al., 2015, pp. 182). After the GFC, the vacuum left after the disappearance and/or privatization of these Saving Banks (and the consequent extinction of the programs they were funding), has been partially occupied by foundations of conventional commercial banks and multinational companies under the framework of responsible banking (Molina et al, 2017, pp. 6). These foundations, supported by local administration and in collaboration with different business schools, started to develop programs to foster social-entrepreneurship by offering access to financing, counselling, training, and networks to “promising” social ventures. The intervention of these agents made social-entrepreneurship appear as a “new” space —a new grammar— where most of the organizations, cooperatives, associations and collectives had to move, redefine themselves, and “compete” in order to maintain their activities (Valenzuela-García et al., 2015, pp. 182). These developments, alongside extreme austerity measures imposed in Spain, have seen many citizens forge new solidarity and alternative economy initiatives, making this generic analytical space of “social economy” even bigger and more diverse.

Interestingly, as a strategy to better tackle all this complexity, the authors of the research conceptualized that space, following Fligstein and MacAdam (2011), as an unsettled Strategic Action Field (SAF) (Molina et al, 2017, pp. 19). In this field banks and multinational companies, foundations, business schools and public administrations alike promote the label of “social entrepreneurship” through diverse incentives. At the same time other groups claiming the same social/environmental goals contest their market-oriented definition of the field (Molina et al, 2017, p.1). The authors of the research stress that the former agents have enabled and stabilized a prescriptive and tautological definition of social entrepreneurship that defines that a social enterprise is any kind of profit or non-profit venture with social objectives (Valenzuela-García et al., 2015, pp. 181). In addition, the concept seems also to fulfil a marketing strategy by associating banks and their foundations with positive social and environmental values precisely in times of a deep discredit and financial downturn (Molina et al, 2017, pp. 20).

In this scenario, as has been done in the Art-Based Social Enterprises Project, the research group made a mapping of the Catalonian social-enterprises that is represented in the image below:

Map of the social/environmental organizations/initiatives in Catalonia. Image elaborated from their database and retrieved from Molina et al (2017, pp. 10)

After completing a complex, mixed method fieldwork (in which together with ethnographies, in depth interviews and social network analyses, they built up a database of more than three hundred social-enterprises), they established an analytical continuum with two extremes. On one side they locate the market oriented social enterprises which more or less fits with the “official” definition of the social entrepreneurship. On the other side they locate the exchange-oriented initiatives that in some cases reject the category of social enterprises. Along this continuum they elaborate a significant analytical typology composed of “the displaced”, “the converted”, “the chosen” and the “challengers” (Valenzuela-García et al., 2015, pp. 183).

The first category represents professionals and other people who used to work as social workers or had a background in integration services. Regardless of their “genuine” commitment to social and environmental values, they seem to have moved to this field adopting the label of social entrepreneurship as a self-employment strategy in response to unemployment, to present themselves well in public spaces, as well as for applying to new funding programs. “The converted” type brings together those non-profit organizations which have transformed to operate as commercial business after the reduction or disappearance of the public funding they used to be supported by. Both “types” have chosen this label due to the positive image associated with it, and because it emphasizes the collective nature of the ventures —in accordance with the strong cooperative tradition in Catalonia (Molina et al, 2017, pp. 22). Those categorized as “chosen” represent those initiatives that fit well with the “official” market-oriented definition of social enterprise. These types have been acknowledged by public institutions and agencies and have received awards and funding that have boosted enormously their capacity of action. In other words, the “chosen” are mainly the ventures that are presented by the media as paradigmatic examples of successful social enterprises. Finally, at the other end of the continuum are “the challengers”, a large, complex range of collaborative initiatives close to anti-market and anti-capitalist philosophies. In developing similar projects, and showing the same post-materialistic values (Inglehart, 1977, 1989) of the other types, they reject the use of the term “social entrepreneurship” in the sense that, among other things, they do not agree with the presence of actors such as banks or foundations in the field (Molina et al, 2017, p. 22).

The authors develop these ideas with more detail, care and accuracy than I’m doing here and I strongly recommend reading their research. Among all the complexities, controversies and problems that revolve around the “landing” of the concept of social-entrepreneurship in Catalonia, it is worth noting how, depending on the background, interests, values and objectives of each agent in the field, this global grammar of social-entrepreneurship acquires different accents, diverse meanings, uses and purposes:

(…) in this complex societal transformation, “social entrepreneurs” are primarily those individuals who are awarded as such by homonymous funding programs. This is mostly an urban phenomenon, whose dwellers are facing profound societal changes, to which they are reacting with initiatives more suited to their values, education, and material conditions of life in a market economy. Possibly, we are facing a global trend. On the other hand, other people with the same social/environmental concerns, and the same capacity to mobilize resources for “changing the world,” are comfortably installed either in the cooperative or in anti-market sectors (Molina et al, 2017, pp. 22).

A number of opportunities present themselves in thinking about the social enterprise field, its emergence in contexts where global social, economic and political disruptions and change play out in different ways in different places, in different histories and different presents. These opportunities include what we can learn from recognising, listening to, and paying close attention to these different vocabularies, these different accents, these different voices. I will explore a number of these possibilities in my final post.

Bibliography:

ALONSO, L. E. & FERNÁNDEZ RODRÍGUEZ, C. J. 2018. Poder y sacrificio. Los nuevos discursos de la empresa, Madrid, Siglo XXI.

BAGLINONI, S. 2017. A Remedy for All Sins? Introducing a Special Issue on Social Enterprises and Welfare Regimes in Europe. Voluntas: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organization, 28 (6), 2325-2338.

BORZAGA, C. & GALER, G. 2016. Social Enterprises and their eco-systems: developments in Europe. Directorate-General for Employment, Social Affairs and Inclusion, Brussels, European Commission.

DELEUZE, G., & GUATTARI, F. 2004. A thousand plateaus: Capitalism and schizophrenia. University of Minnesota Press, London.

ESPING-ANDERSEN, G. 1990. The three worlds of welfare capitalism, Cambridge, Polity Press.

FLIGSTEIN, N., & MCADAM, D. 2011. Towards a general theory of strategic action fields. Sociological Theory, 29(1), 1–26.

INGLEHART, R. (1977). The silent revolution. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

INGLEHART, R. (1989). Culture Shift in Advanced Industrial Society. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

KELLY, P., & PIKE, J. (Eds.). 2017. Neo-Liberalism and Austerity. The Moral Economies of Young People’s Health and Well-being, London, Palgrave-Macmillan.

LOREY, I. 2015. State of Insecurity : Government of the precarious, London, Verso.

MOLINA, J. L., VALENZUELA-GARCÍA, H., LUBBERS, M. J., ESCRIBANO, P. & LOBATO, M. M. 2017. “The Cowl Does Make The Monk”: Understanding the Emergence of Social Entrepreneurship in Times of Downturn. VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, Special Issue, 1-24.

VALENZUELA-GARCÍA, H., MOLINA, J. L., LUBBERS, M. J. & LOBATO, M. M. 2015. Empresas sociales en Cataluña. ¿Cambio de paradigma o estrategia de clase media? Otra Economía,, 9, 177-186.